Do you ever wonder how many television sets he's sold, how many wives have been told "shut up, he's batting", how many prayers are intoned in every language and faith when he comes to the crease? Do you ever wonder when last a man evoked such unreasonable passions? Begin this journey if you will in a child's bedroom. Ranvir Banerjee is 13, lives in Hyderabad, genuflects when Sachin Tendulkar bats, weeps when he's out and won't watch him at the stadium because the last time he did Sachin was out for a low score, so there's some bad karma at work here. Forget his poster that reads "The Only God", forget the underwear with His Holiness' face on it, one answer the boy gives reveals best this obsession, this aura of invincibility Sachin is seen to wear. Is Sachin better than Donald Bradman (when clearly he is not), merits this reply: "A 100 per cent. There couldn't have been anyone better, he's perfect."

This perception is not reflective of a child's worship; it speaks of a national affliction. Why? It's hard to say. Maybe it's the absence of heroes that enhances his appeal. Only the film actor draws similar obeisance, but he provides fantasy; with Sachin there's no need to let the imagination slip, his art is real.

We'd had majestic cricketers before too, some cited even as better than him. Yet with Sunil Gavaskar (his face on underwear!) you got the immaculate craftsman, a lesson in science. With Sachin we got the smell of something more foreign.

The phenomenon.

That unlikely confluence of an uncommon man and changing times.

That unlikely confluence of an uncommon man and changing times.

It was the age that caught first attention for there is nothing that excites like the prodigy. It is beauty in all its newness, it is flamboyance that understands no shackles. For the young this was marvellous. They read stories about a nightwatchman hearing noises on the roof at midnight and finding it was a restless Sachin practising. God, a kid just like them, a worthy carrier finally of their teenage dreams.

Grown-ups are startled too, for to a sporting land where the men lacked adequate resolve this boy brought a strange assurance. Waqar Younis made his mouth bleed on his first Test tour, a baptism we flinched from but he, 16, didn't. He felt fear, he once admitted, but fear only that that his first Test, where he scored 15, would be his last. There was another thing too: he was not big and strapping, no young Jacques Kallis who surely lunches on raw crocodile liver. And so the contrast, between this choir boy with the reedy voice and his authority on the pitch, made for dazzling theatre. You had to be moved. One umpire tells a story that twice he did not give a youn g Sachin out LBW, because he so enjoyed watching him play.

g Sachin out LBW, because he so enjoyed watching him play.

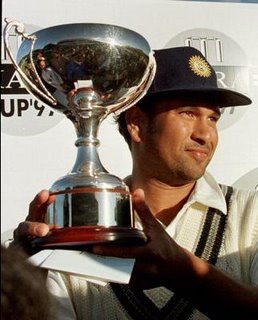

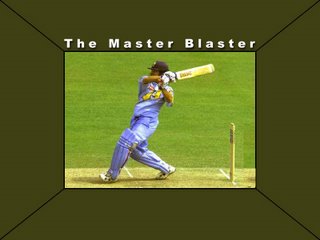

But youth vanishes, replaced by stubble, and with it the romance seems to slip. But Sachin seemed to hold us in his thrall by reason of style. In an aggressive time his art was suitably violent. In an era of power, he was cricket's poster-boy of destruction. This was an age of not holding back, and he defined it by launching into shots that defied conventional imagination (how could we say he took a risk when our definition of the word never met his). His cricket, all magical mayhem, fit his times.

It was important, for though he was artful too, we'd seen it before; this sending of Kasprowicz to the moon, and Warne to the sun was mesmerising. As the ball soared we soared too. Men would not dare go for a pee for fear of missing something. Stunned, Greg Chappell once said, "I'd like to watch him bat with one stump." If, in these '90s, Sachin played like Gavaskar he would not have been a phenomenon.

There was one last thing. A young new-age hero needed his medium and in tv he found it. In a distracted world of the '90s, our lives cluttered by information, demonstration of genius was important. To spread his gospel further and quicker, Sachin required pictures.

The timing was perfect. In 1993, as England toured, and his batting began to find mature flourish, India embraced Star Sports. Every stroke was explained, every stroke shown, from the sides, in front, on top, behind, the mechanics of his brilliance on continuous display. And through the years as he did it again and again and again, we were there with him.

mechanics of his brilliance on continuous display. And through the years as he did it again and again and again, we were there with him.

It wasn't only cricket either. Every day he wandered into our living rooms, selling music machines and drinking Pepsi, transformed into India's pre-eminent corporate pitchman. He had no personal style, no obvious charm, if anything there was a blandness to him. It was a sensible, and perhaps purposely constructed, image. Always neatly dressed, no earring in the ear, no arrogance, never controversial. An enraptured India had found an icon who was just the perfect contradiction: a freak but a wholesome one.

What is exhausting, scary, is that at 26, we have so much to say of him, and he is not done with cricket yet. How many more bowlers must tremble, captains worry? How many more wives will be told to shut up, "He's batting"?.

1.Tendulkar has been seen taking his Ferrari 360 Modena for late-night drives in Mumbai. (Gifted by Fiat through Michael Schumacher, the car became notorious when Tendulkar was given customs exemption; Fiat paid the dues to end the controversy.)

1.Tendulkar has been seen taking his Ferrari 360 Modena for late-night drives in Mumbai. (Gifted by Fiat through Michael Schumacher, the car became notorious when Tendulkar was given customs exemption; Fiat paid the dues to end the controversy.)

to have her as a life partner, because when I go on the cricket ground I don't have to think of anything else because I know she would handle everything to perfection," Sachin said in an interview.

to have her as a life partner, because when I go on the cricket ground I don't have to think of anything else because I know she would handle everything to perfection," Sachin said in an interview.